On a typical day in the Chinese city of Wuhan, hundreds of patients undergo minimally invasive image-guided therapy to get treated for heart, vascular, or brain diseases. That number dropped close to zero at the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, as all non-urgent procedures came to a sudden halt in an effort by hospitals to focus on the critically ill, prevent the most vulnerable from incidentally contracting COVID-19, and preserve scarce supplies such as masks and gloves. We have seen the same pattern unfold around the world: as healthcare systems are forced to channel their efforts into combating COVID-19, non-urgent procedures are suspended – deferring patients with other illnesses to the waiting room when their condition allows for it. But how long can these patients wait before it’s too late? It’s a dilemma that interventional physicians like myself are grappling with, and that hospital administrators will also recognize as we are all working around the clock to balance the needs of COVID-19 patients with those of countless others requiring timely treatment. Non-urgent doesn’t mean optional. Take for example the early-stage cancer patient whose initially indolent tumor is growing. Or the patient with an aortic aneurysm, now harmless but potentially fatal if left untreated for too long. We have to ask ourselves how we can continue to provide care to patients like these, while continuing to curb the pandemic.

Non-urgent care doesn’t mean optional care.

While I don’t pretend to have definitive answers, I have seen some inspiring examples from peers around the world on how they are dealing with this dilemma. These examples reveal three priorities: (1) preserving patient and staff safety; (2) promoting collaboration between hospitals and outpatient interventional centers; and (3) virtualizing care whenever possible. Let’s explore each in more detail.

1. Preserving patient and staff safety

Over the past weeks, my peers and I have been confronted with a radical new reality. Some of us have continued performing emergency procedures on patients with acute conditions such as stroke (which cannot wait, because ‘time is brain’). Others have stepped in as intensivists in the ICU, helping out overworked colleagues at the frontlines of COVID-19. Still others, myself included, have been forced by local health authorities to quarantine for 14 days after being inadvertently exposed to COVID-19 victims.

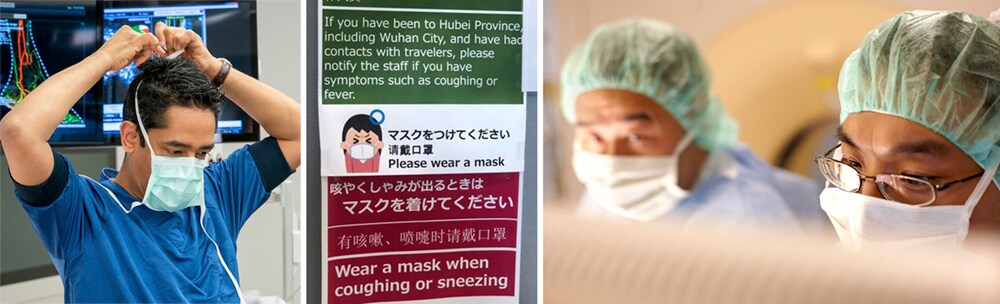

Whatever our individual roles and experiences as physicians, all of us have been acutely reminded of our responsibility in safeguarding patient and staff safety. Minimizing the risk of crossover infection will remain a key priority until effective treatment medications and a vaccine are found, or until we have developed herd immunity.

All of us have been acutely reminded of our responsibility in safeguarding patient and staff safety.

Already hospitals are taking great care to physically segregate COVID and non-COVID patients, with thorough triaging. Asian countries like Singapore were relatively well-prepared based on their experiences during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Since then, major hospitals were renovated to set up interventional departments on nearby yet separate floors – making it easier to treat infected and non-infected patients separately, should the need arise. Hospitals in the Western world are now also going to great lengths to avoid cross-contamination, as this report from Italy illustrates in more detail.

While personal protective equipment (PPE) remains scarce, I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to make PPE available for all healthcare workers who have direct patient contact. This includes non-medical staff, as physicians from Singapore remind us based on their learnings from the SARS outbreak. Looking forward, I am keeping a keen eye on the advent of rapid (<15 min) fingerstick testing – both to diagnose active COVID-19 infection and to identify staff and patients with presumed immunity. On April 15, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also approved use of a saliva test to detect COVID-19, helping preserve both the safety of medical professionals and valuable PPE. Once the pandemic abates and a staged return to normal becomes possible, rapid testing could help to create “clean zones” in hospitals for resuming elective procedures. Yet we will have to be even more creative – and think expansively about what care gets delivered where.

2. Offloading hospitals through creative collaboration

Around the world, we are seeing the value of collaboration as overburdened hospitals look for ways to transfer patients with conditions like cancer, stroke, and heart disease to locations where they can still get the specialized therapy they need. In the US, certain procedures are now moving to outpatient settings such as office-based labs and ambulatory surgery centers. These facilities, which have been growing in number for over a decade, can help to offload hospitals while offering an alternative for patients who would otherwise suffer from a delay in care. (Physicians at office-based labs recently shared how they are coping with the pandemic in a webinar hosted by Philips.)

Outpatient interventional centers can help offload hospitals while offering an alternative for patients who would otherwise suffer from a delay in care.

The shift to outpatient settings is actually not a new development. Over the past years, the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have set the stage for it through reimbursement policies that promote the performance of certain procedures in outpatient settings. The COVID-19 crisis is now acting as a major accelerator of this shift. On March 30, CMS announced sweeping regulatory changes under the Hospital Without Walls program, making it easier for hospitals to transfer patients to outpatient settings or to set up their own ambulatory surgery centers.

In Germany, first networks of outpatient interventional centers have also emerged in recent years. It will be interesting to see how this trend plays out in Europe in the aftermath of the pandemic. In the short term, regional collaboration between formerly competing hospitals can help to reallocate patients and supplies when needed. Importantly, in the US, physicians have been temporarily permitted to practice across state lines, without having to go through a costly and time-consuming application for a state-specific license. I have a professional license in Pennsylvania, yet I can now practice in New Jersey. Obviously, travel limitations may still impede our flexibility. But the temporary lifting of regulatory restrictions applies to telehealth as well – allowing us to virtually support our peers across the country as the demand for COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 related care continues to change over time and across states.

3. Virtualizing care: from novelty to necessity

Will telehealth now finally go mainstream? Like many other disciplines in healthcare, interventional physicians are transitioning to virtual ways of staying in touch with patients and with each other. Earlier this month, the American College of Cardiology reported that in cardiovascular care, 69% of providers are now using telehealth services.

When patients have to wait for elective surgery, regularly checking in with them can help to keep a pulse on their condition, intervene when needed, and hopefully alleviate some of their distress. Based on my own experience, patients are very receptive to this development. They welcome the opportunity to have a video chat with a physician without having to leave the house and sit in a waiting room for 20 minutes. With telehealth moving from novelty to necessity and being embraced by patients and physicians alike, I don’t see us fully going back to how we did things before. At the same time, we need to be mindful that not all aspects of care can be digitized. For example, in some initial patient consultations or post-procedure visits, I still prefer to examine the patient physically to do a thorough pulse exam or assess for post-procedure complications. Telehealth is a tool, not a cure-all. It will never fully replace the physical touch that is so vital to our work, and the emotional connection that can only be established through real face-to-face contact.

With telemedicine now being embraced by patients and physicians alike, I don’t see us fully going back to how we did things before.

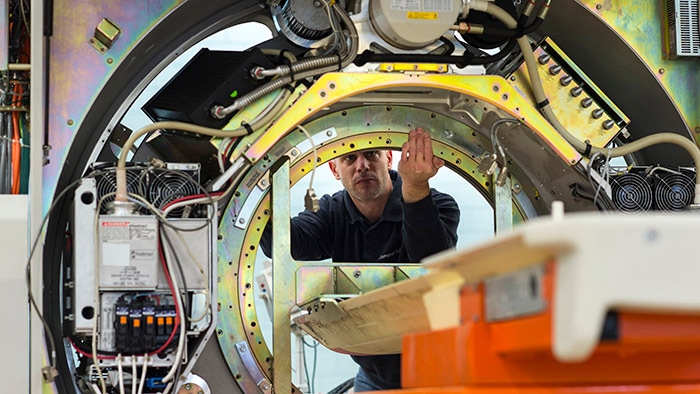

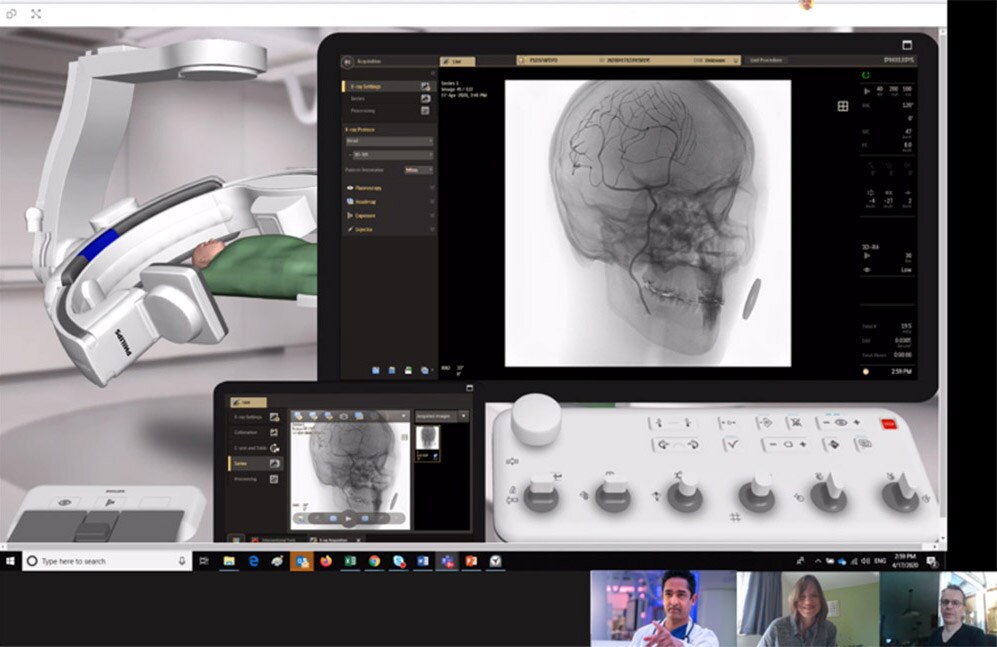

Yet the value of instant and immersive virtual connection is undeniable, especially in times like these. Healthcare workers now also rely on it for education and peer-to-peer collaboration, which is why Philips is accelerating its virtual offerings to them. For example, we have started digitally streaming in our application specialists into the operating room to provide physicians real-time support. And we are even enabling physicians to test-drive our interventional systems from continents away, using mobile robots with cameras and cloud-based simulators.

Virtual experiences such as these will become even richer as we continue innovating towards the future. Ironically, just before the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in the US, I was invited by the FDA to speak about the promise of augmented reality to help interventional physicians look through each other’s eyes. Wearing a head-mounted display, physicians will be able to share what they are seeing in real-time and consult their peers for advice as they are operating on a patient. While this technology is work in progress, the current predicament strengthens my belief how important it is we keep advancing such innovations – to bridge physical distances with virtual solutions.

Preparing for the light at the end of the tunnel

Of course, huge challenges remain in the here and now. As we continue to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of patients with other illnesses who are having their procedures delayed will keep growing. This will be a trying time for many of them. None of us can really be sure how long this situation will last. Or when hospitals around the world will be able to resume procedures again. One thing I am sure of is that there will be light at the end of the tunnel. And we need to be prepared for that. Because there is a moment when many elective procedures become essential too. Patients with early-stage cancer or an aneurysm in the aorta cannot wait indefinitely before they get treated. We owe it to these patients to start rescheduling planned procedures again as soon as we can.

There is a moment when even elective care becomes essential.

The first glimmers of hope are already there. In the U.S., guidelines have been laid out for a phased approach to resuming non-urgent procedures in hospitals when and where possible. Similarly, in Australia and Italy, hospitals are finalizing roadmaps to restarting these procedures. And in parts of China, non-urgent procedures have already resumed. I’m hearing from colleagues there that physicians are going the extra mile – working weekends and extra shifts – to tackle the backlog of patients who’ve had their care postponed. It’s another testament to the unwavering commitment of hospitals and healthcare workers worldwide – not just in fighting COVID-19, but also in making sure that no patient is forgotten.

Share on social media

Topics

Author

Atul Gupta

Chief Medical Officer, Image Guided Therapy Atul Gupta, MD is Chief Medical Officer at Philips’ Image Guided Therapy and a practicing interventional radiologist. Prior to joining Philips in 2016, Atul served on Philips’ International Medical Advisory Board for more than 10 years. Atul continues to perform both interventional and diagnostic radiology in suburban Philadelphia, in both hospital and office-based lab settings. He has been repeatedly recognized as top physician for his specialty in the media and serves on several advisory boards. He has also published and lectured internationally on a range of interventional procedures.

Follow me on